During the height of the millennial drought, I was peripherally involved in one of the side skirmishes of the “Water Wars” playing out across rural and urban Australia. Some of my talks, teaching and writing1See for instance Gardening Australia with Josh Burn at Melliodora in 2007 and ‘Garden Agriculture: a revolution in water use efficiency’ (2005) focused on introducing water allocations for suburban residents instead of the selective restrictions that allowed spa baths but prohibited food growing. At the same time, the bigger battles were being waged over the Murray-Darling Basin Plan (MDBP) controlling 70% of Australia’s irrigated agriculture.

With a couple of colleagues close to the frontlines I was vaguely aware of the massive human and other resources being expended to guide and justify the decisions under the regime of “administrative rationalism” that required the Plan to be guided by the best science. Retrospective evaluation by the South Australian Royal Commission showed that the Murray-Darling Basin Authority was negligent in ignoring climate modelling of a drying climate in favour of using the 114 year historical record of river flows as a basis for the plan. After spending $13 billion dollars of public money, the public got a corrupt plan made law by the federal parliament.

Maybe my sense of this dysfunction at the top contributed to my own back-of-the-envelope plan for not only the Murray-Darling but the whole nation’s water resources. In some presentations I jokingly referred to how I would solve the national water crisis when I became dictator.

For me this tongue-in-cheek exercise illustrated Bill Mollison’s assertion that “while the problems of the world are remarkably complex, the solutions are remarkably simple” might be true, at least in some cases. On the other hand, my follow up point was that the rapid implementation of my plan under dictatorial powers would inevitably have both predictable and unpredictable consequences, capable of generating chaos in psycho-social, political, economic and ecological systems more intense than the grinding dysfunction of current notionally democratic governance systems.

With the wisdom of hindsight dissecting the dysfunction of the MDBP, I’m now putting “Dictator Dave’s National Water Plan” on the record.

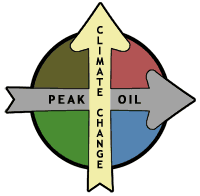

In contrast to the MDBP, which managed to ignore the consensus climate modelling, my plan is predicated on my long-standing assumption of Energy Descent Futures2See for instance futurescenarios.org; for a more concise and updated essay see ‘Futures framework for RetroSuburbia: limits to growth, energy futures and energy descent scenarios’ at retrosuburbia.com that incorporate climate change, resources depletion and other critical limits to global growth economies articulated in the seminal Limits to Growth Report of 1972.3Meadows et al Limits to Growth Report (1972)

Current Realities

Agriculture uses 70% of Australia’s impounded and diverted water while residential use is about 12%, so agriculture, and land use more generally, is clearly the focus of my plan.

Much of agricultural use goes to exported products, which allows Australians in turn to buy imported widescreen televisions and cars. We could thus reduce the need to suck the country dry by being more frugal in our demands for imported products. Let’s assume about 50% of water is used in this way, and could be saved by changing our consumption patterns.

If the other 50% of agricultural use is for our Australian food supply, then changing our eating habits could have a much bigger impact on water demand than showering times and frequency.

Irrigated pastures and fodder crops for livestock consume 35% of Australia’s water, so eating less dairy and avoiding feedlot beef could have a huge impact on water use.4Grazing livestock on rainfed pasture and rangeland occupy the majority of the continent and if you include all the farm dams and bores supplying stock water it’s quite a lot. However the water in those small dams scattered across the country has many environmental benefits, including supporting native wildlife, so in my plan that doesn’t count as impounded and diverted water, while the majority of farm dam water (9% of total in Murray-Darling Basin) used for irrigation of crops does.

Changing to goat dairy could also make a big impact since goats are better adapted to unirrigated pastures and fodder.

Sugar cane uses an amazing 17% of Australia’s impounded and redirected water. We would be better off consuming a lot less sugar.

Rice grown in the semi-arid zone of the Murray-Darling Basin uses 11% of our irrigation water. Shifting rice growing the summer rainfall regions of northern NSW and Queensland could eliminate this demand and replace sugar cane.

Cotton uses 10% of our irrigation water. While we need food to be grown every year, Australians probably have enough clothes between us for the next decade at least, if the figures published in the War On Waste are any indication.

If Australians used their existing town, tank and storm water resources, as well as recycled greywater, to grow food not lawns, we could close down at least half of the remaining irrigated horticulture in rural areas by growing veggies, fruit and raising poultry for eggs and meat. The prime agricultural land freed up in this way could be returned to dryland staple grains and legumes, allowing a larger area of low rainfall marginal cropping land to be returned to permanent pasture and/or revegetation.

So when Dave is dictator, the National Water Plan will include the follow measures:

- Replace the 50% of Australian sugar production that uses the most irrigation water with dryland rice, after ending all water allocation to rice growing in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation District and taxing the hell out of sugar (as well as outright banning high fructose corn syrup), to encourage the sugar addicts to consume less, and to switch to honey from a more sustainable and beneficial industry that consumes very little water.

- Ban the export of powdered milk and eliminate all irrigation for dairy production, aiming to reduce cow dairy production by 75% and encouraging dryland goat dairy to increase enough for Australians to eat about 50% of the dairy they currently consume. 50% of the increase in goat dairy would be in peri-urban herds where the goats also replace herbicide for vegetation control (because Dictator Dave will have also banned glyphosate).

- Close down all beef feedlots, which will save water and also conserve grains not suitable for human consumption for the more efficient use of feeding free range poultry and pigs.

- Grazing of rainfed pastures and rangeland will continue to be the predominant land use but with policies to shift the balance to more harvesting of wild meats with fewer cows and sheep. Australia will continue to export surplus meat from these systems.

- With the cessation of cotton production in Australia, the plan will include scaling up a hemp growing industry to more efficiently make use of some of our best cropping soils for sustainable fibre, oil seed and pharmaceutical production while providing a disease break rotation from grains, legumes and oil seeds.

That’s the bare bones of the plan, which will save about 40% of Australia currently impounded water. This is roughly what some of the climate models suggest will be the reduction in available surface waters before 2050. Given that water allocations are currently unsustainable we might have to implement further savings.

For example, savings could be achieved through changes in behaviour away from wasteful habits such as showering every day and washing clothes excessively, which are currently encouraged by the reliable delivery of treated town water at pressure for not much more than $2/tonne. With more people working from home, the obsession with these activities might fade with the rise of neo-peasant living in retrosuburbia. To accelerate this natural transition, Dictator Dave might mandate the closure of water treatment plants so reticulated water might not be crystal clear for washing or suitable for drinking, but remains cheap and abundant to encourage garden farming. Rainwater tanks with simple first flush diverters can provide potable water, with filters where necessary for the microbiologically challenged and those addicted to whiter than white clothes.

Compost toilets managed by some eco version of the night cart service will progressively replace most flush toilets, saving shitloads of water and recycling critically important phosphates and other nutrients back to the land that feeds the people.

Of course lots of industrial water use, including in the power generation sector, will be gone with the closure of many coal power plants to radically reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

At the same time eco technologies such as biochar, riparian rehydration, silvopasture and keyline adopted by farmers will act as partial alternatives to irrigation and as a hedge against further aridification of the continent while gradually increasing sustainable food production. This will feed the slowly growing population resulting from the acceptance of a fair share of global refugees. Along with a larger proportion of Aussies, these refugees will be mostly working the land rather than the office and the factory because when Dave is dictator, it will be simple and logical.

No it won’t – whatever happens, it’s going to be messy. The responses to Covid have been the great accelerators in the rise of disaster capitalism and command economies replacing market solutions. As the multiple interlocking crises of the Brown Tech future scenario continue to erode faith in democratic representative governance, command-and-control politics in some form will be what the public is likely to accept and favour. Even the most well intended and best efforts at command-and-control governance responding to multiple unfolding crises will have unintended consequences and collateral damage. And of course unrestrained power over people and land will always tend to corrupt and bring forth those aiming to game the system for private rather than public good. Such is life.

While this thought experiment is just that, I believe it is more constructive in thinking about our future use of water in Australia than the $13 billion and untold intellectual effort and angst that led to the MDBP.

Rather than big bold top-down responses to crises, permaculture ethics and design principles suggest a proliferation of diverse bottom-up responses as richly illustrated and fostered in RetroSuburbia: the downshifter’s guide to a resilient future.

One of the spinoffs of that book was the essay Feeding RetroSuburbia; from the backyard to the bioregion written to help those engaged in garden farming see the other parts of the puzzle of a regenerative and resilient food system. Rather than imagining a top-down mandated change along the lines of Dictator Dave’s National Water Plan, I envisage a bioregional food system growing in the shadows of the globalised system. In this vision, the bioregional parallel system might be feeding 20% of the population of Melbourne and regional Victoria within 20 years.

My assumption is that the increasingly stressed centralised system will be propped up, with feeding the masses as one of the last remaining functions of command-and-control governments. Whether the parallel system grown from grassroots can replace the failing centralised system in another decade or so, and feed everyone without radical breakdown in society, is too difficult to forecast. I do see this pathway as much more achievable, realistic and benign than big bold and enforced top-down plans, whether inspired by permaculture, such as the Dictator Dave thought experiment, or the supercharged plans unfolding from the World Economic Forum and other venues of elite power.

Just maybe the small and slow solutions will prevail, just as in the fable about the tortoise and the hare. And even if they don’t, they will become the lifeboats and seeds for the regrowing of the more localised and re-ruralised communities that our descendants will live in, whether by design or disaster.

David Holmgren

Winter 2022

(Published 2023)

12 thoughts on “Dictator Dave’s National Water Plan, and more modest musings”

Brilliant.

I’d vote for you.

Surprised to learn only 12% for residential use. Nevertheless, huge fan of compost waterless loos. Rain water tanks. Banning black rooves which is not so much about water so much as cooler urban ambient temps, maybe less garden watering.

And to other matters –

Divert $$ from fossil fuel to subsidised solar for all. Sadly this will increase need for those rare minerals so recycling is essential.

Mandate better home design to rid us of the curse of mcmansions greedily sucking too much resource and power. Children do not need their own room and bathroom for Pete’s sake.

Set up Homeshare to help keep elderly in their home while sharing larger homes, of course entirely voluntary.

Love the plan and the insights and statistics on national water usage.

Related to water use on the home scale, I’ve been recently energized by the syntropic agroforestry approach developed in Brazil.

I’m very impressed with its design for efficient management and the focus on support species to build an ample and ongoing thick mulch layer in the orchard.

Currently in the process of testing a number of support species to see what thrives in the local climate. Yacon, mexican sunflower, sunchoke, tagasaste, and succulents are some of the test subjects.

Also testing the fast growing Eucalyptus Nitens which is renowned for biomass production but perhaps too water hungry, we’ll see. In Brazil they rave about it from what I’ve read.

From what I’ve experienced in the garden here in Victoria, thick mulches are very effective for keeping the fruit trees hydrated and keeping the grass at bay. Hopefully our collective efforts as a permaculture community will ease the burden of the Energy Descent future.

Kind of reminds me of Isaac Asimov’s Hari Seldon and the Foundation attempting to buffet the galaxy’s suffering by speeding up the dark period in it’s fated collapse. Instead of warp drives, nanobots and sleep pods we have swales, perennial pastures and hardy bioregional genetics 😉

Excellent article as usual !

Doesn’t this fly in the face of the maximum power principle though?

Those states who hold onto their large scale irrigated agriculture the longest will be at a massive advantage. The irrigation schemes do offer some protection against drought, and if the rest of the landscape is parched being able to irrigate will make these places seem like oasis. The Murray Darling Basin and its schemes (especially the snowy hydro ) therefore looms as a hotly contested region in decline scenarios. In the longer term future where international trade breaks down the basin could establish itself as one of the dominant regions on the Australian continent due to the legacy irrigation infrastructure, and harden into a centralised society seen in other irrigation cultures like Egypt and the China of the northern plain. This region would therefore be able to militarily dominate other regions that are less centralised. Cynical vision for sure, but history seems to point that way.

Thanks for your question and future scenario. I agree your scenario is one that could play out in the longer term. However leaving aside the Swiftian satire aspect of my piece, conserving water to align with what might be available in the relatively near future can be a pathway to maximum power. Reallocating water from less useful to more beneficial uses (eg from sugar to rice or cotton to hemp) can also maximize power. Winding back cow dairy production and consumption in favour of goat dairy and tree crops could improve population health and consequently systemic power. Beyond these rather conventional options, it is even possible that reallocating water back to “environmental flows” could increase biological productivity, that could in turn generate future resource wealth, even if those resources are so diverse and distributed as to be only suitable for harvesting via localised non monetary economies. So in these ways, I doubt the “enlightened collective self interest” that I am trying to illustrate contradicts the idea that the Murray Darling Basin could become a power centre with influence across the Australian continent long after the non renewable resource are depleted. Whether that influence is benign and beneficial or exploitative and oppressive might be in the chances and trajectories of history beyond any of our speculations.

Thanks for the response David.

I agree that all these uses you mentioned are more efficient and have the potential to actually maximise power, it’s just that I see the large scale irrigated districts incentivised to continue to irrigate with vast amounts of water in a Jevons paradox style, using centre pivot and lateral irrigators for enormous cereal grain production plus almonds and nuts all for the export market (both of which are expanding as we speak, particularly summer irrigated crops like maize and even soybeans are being proposed for the dreaded midwestern combo) which is a more efficient use of water but may lead to increasing inputs and if expanded only a small change in overall water use for agriculture. A lot will depend how much longer fossil fuels and electricity stay cheap enough to make it profitable.

Being from the area and living deep amongst these irrigation schemes I’ve seen some changes over the last decade or so that match up both with parts of your vision and follow a systemic response along the lines of Odum’s work. To me the dairy farms were the natural outcome of what amounted to unlimited water availability for irrigation on the best soils, as it produced a high value product with great transformity. But in a similar way to other systems with huge throughput of energy (in this case in the form of water), it created a low diversity and wasteful environment.

Since the millennium drought and tightening of water availability through the creation of the water market there has been a large decrease in the number of dairy farms and the energy throughput of large scale flood irrigation, but an increase in diversity of farm operations. There are far more nut plantings and mixed enterprises. In many ways these old dairy farms are the prefect sites for more rebellious independent minded types to try out new ideas on good soil with the help of much more modest irrigation than the past.

From a certain deep time perspective the dairy years may have been a regional ‘pulse’ of high energy inputs that increased soil fertility and overall biological productivity of the area by seeding it with high value naturalising legumes such sub clover, lucerne and vetch. More diverse land uses can build upon this base that use water more efficiently.

(I’ve often thought about this regarding Australian agriculture as a whole, with the fossil fuel powered fertilising of the last century pulsing our geologically old soils, particularly with phosphorus and calcium that was lacking. Maybe Gaia found a way to use us?)

Interesting article and an increasingly urgent challenge particularly with a record approx 500,000 migrants to Australia this year, increasing the burden on these resources.

I would like to emphasise some other points which in my view can provide possibilities and direction for positive action.

1. Water doesn’t disappear- It changes location and changes phases.

E.g. We currently have rising sea levels and a warming atmosphere which holds more water vapour. This further warms the atmosphere which holds more moisture. A warmer atmosphere makes cloud formation more difficult and water vapour increases. As a generalisation precipitation events become less frequent and more severe. A positive feedback loop. Groundwater is being depleted rapidly through pumping. Again more water from the land going into the ocean and the atmosphere.

Hopefully one day the national strategic emphasis will be on how we steward our landscapes so that the water from the ocean and in the atmosphere can participate more in the small water cycle.

Importantly each individual or collective has the capability to innovate or improve their own context. Permaculture emphasises and teaches this very well.

2. There is hope. All is not lost in a degenerative spiral of ecological dysfunction.

Living systems are dynamic. There is no static point in the past where they peaked. We can enable Nature to create topsoil or rapidly restore healthy water cycles.

Sometimes I hear permaculturalists or Regen Ag advocates say that a previous abundant ecosystem and incredible fertility from the past can’t exist again. When in fact if we steward our land for more life and diversity it is not only logical but inevitable that abundance, fertility, diversity and ecological function beyond what has existed can be expressed.

Many people around the world face extreme water challenges today and increasingly so in Australia.

This has the motivation for a startup company my co-founders and I have formed. PSKL – Water For All Pty Ltd. We focus on rapid infiltration and pumping of extreme runoff or snow melt in some innovative ways. The can help reduce drought, fire, flood and a changing climate. Strategies are focused on increasing the biotic pump effect and bioprecipitation. There are many interconnected benefits.

Example strategies: Desert to Rainforest https://drive.google.com/file/d/14MXQPJyW8FSJ6F1rmFyMPV5J7RF787tt/view?usp=sharing

x100 Infiltration TIME- https://drive.google.com/file/d/1CwG_JtZ4yCqA1oKzsrmJN9yMzelMrZ2l/view?usp=sharing

Snow Melt – https://drive.google.com/file/d/12TZ3pdhhH7gN9HJJ0-pBXejVjLI4kigY/view?usp=sharing

Happy to hear your anyones feedback or questions

Thanks David for your incredible body of work and inspiration. 🙂

Steve

PSKL – Water For All Pty Ltd

Steve,

I agree that there are many strategies to restore and regeneration land beyond efficient national land use allocation that I focused on in this essay (to illustrate the risks in doing anything fast and at massive scale). I also agree there are many ways to increase the biotic pump and it looks like your designs for combining water harvesting and storage earthworks and simple low tech hydraulic powered pumps could make a great combination in many situations even if I am a bit skeptical about the degree to which the desert to rainforest visions can apply across landscape rather than “oasis” models such as researched and demonstrated in the Negev desert in the 1950s and 60s by Michael Evenari and others. More recently Geoff Lawton’s project in Jordan used some of the same principles of harvesting water from large areas lacking any vegetation to support growth including food trees in very small areas. However in already better vegetated country (most of Australian arid and semi arid areas) the runoff yield is substantially less and even more episodic. When combined with ancient worn out soils (in contrast to many of the geologically young soils of the Middle East arid regions) the prospects for food are more limited although reafforestation providing many environmental services and some yields from rangeland animals and biomass are certainly achievable. I would certainly be interested to see any documentation on projects however modest that have applied the approaches you are advocating.

Here is a really interesting calculations doc from Rob de Laet and others emphasising the main contribution to cooling and moderated precipitation being water phase changes and cloud formation rather than biomass sequestering carbon (though also important.)

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Ae_gjZ8b06Yeupa_ma3MzmDS4ph5lXKG/edit?usp=drivesdk&ouid=117899732130834555024&rtpof=true&sd=true

Steve,

Thanks for that paper. I agree that the dynamics of atmospheric water vapour could be a blind spot in orthodox climate models (although I have know capacity to assess those models other than to question the assumptions) and that the potential to influence the climate through landscape rehydration is a very important opportunity that should receive a lot more attention and resources. Although the dehydration/rehydration process affects the local and potentially bioregional rather than global climate, dehydration of landscapes has been so widespread that it adds up to being global in scale. Like the opportunities the rebuild lost organic matter from most of the worlds cropping and grazing soils, the opportunities to rehydrate previously dehydrated landscapes should be possible, even if turning true climatic deserts into verdant forests might be more difficult. The potential amelioration of local and bioregional climates through rehydration avoids the “tragedy of the common” problem associated with reducing greenhouse gas emission (ie Will reducing our GGE in central Victoria or even Australia ameliorate our climate?) According to orthodox science the answer is no unless the whole world does it.

One of the reasons global capitalism and central governments ignore most of the real solutions to environmental crisis is those solutions tend to be low tech, distributed and particular to place and context. The current focus on high tech solutions that are controlled by global scale players is, I believe, no accident. Whether that results from self organisation (eg Adam Smith’s invisible hand of markets) or conspiracy by powerful actors or some combination of the two, is much less important than recognising this dysfunctional pattern and acting accordingly. Unfortunately the great majority of environmental activism tends to reinforce rather than subvert this pattern.

The problems with any top down managerial fixes to water allocation that I raise in this piece (even those informed by permaculture) reflects a larger structural hubris on the part of global elites in the efficacy of top down management. In a recent essay Laughter of Wolves, https://www.ecosophia.net/the-laughter-of-wolves/ John Michael Greer shows how muddling through has a much better chance of success in a world of energy descent that top down management informed by any particular ideology or set of principles principles. His reference to classic examples of ecosynthesis creating novel ecosystems (Ascension Island and the Wolves of Chernobyl) is perfect in showing how we should follow nature’s path of adaption. Highly recommended reading!