You can listen to David reading this piece here:

Is wood smoke as bad as George Monbiot claims?

In a recent article published in The Guardian, George Monbiot admitted his shame at having installed wood stoves,1“Wood heaters” in Australian English as part of a home energy efficiency retrofit back in 2008. Beyond his shift from thinking wood heating was good to thinking it’s bad, he was raising the flag for a ban on wood (and wood pellet) fuelled stoves in the UK. The reasons for him coming out on this extreme shift in attitude included cheaper higher-tech alternatives and doubts about the sustainability of his local wood supply, but mostly focused on his concerns about the contribution of wood burning to indoor and outdoor air pollution.

As a strong advocate of wood energy, I was recently asked about my response. It’s been twenty years since I challenged the idea that natural gas was better for the environment than wood. Over the years I have been quoting a CSIRO lifecycle study of wood burning in Australia showing commercially harvested wood transported 400 km and burnt in a 60% efficient space heater is a small fraction of the GHG emissions of natural gas (Paul et al, pdf download). Natural gas was favoured by “progressive environmentalists” at the time for generating one third the GHG emissions of coal-fired electricity in Victoria. On tours of Melliodora my spiel about the benefits of wood has often drawn surprise and, at times, disbelief. More recently, I made a strong case for “Wood Energy: the other solar energy revolution” in RetroSuburbia 2Holmgren (2018) RetroSuburbia: the downshifter’s guide to a resilient future, Melliodora Publishing, Chapter 6as a sensible choice for the downshifting retrofitter guided by permaculture ethics and design principles.

While RetroSuburbia is clearly focused on practical low-tech solutions that reduce our dependence on globalised manufacturing, I did end the chapter (p. 124) with a small nod to all the ongoing advances in wood burning technology:

And if energy descent doesn’t turn out to be as severe as I expect then you might be getting electricity, heat and refrigeration from a pellet burning trigeneration unit imported from Europe!

Apparently not, if Monbiot and a constellation of well-funded renewable technology researchers, green tech evangelists, environmental health advocates and online influencers can help it. But to be frank, I accept that my answers to the concerns about the health effects of wood smoke have been the weakest part of my advocacy for wood. There are several reasons for this:

- Firstly, health is not my area of expertise, while the other end of the business, ecologically sustainable forestry, is close to my heart and the origins of permaculture3The conception of permaculture as redesigning farms to be more like forests was informed by the observation that eco-forestry, while not the norm, was inherently easier to achieve than the best examples of eco-agriculture based on annual crops.

- Secondly, health is perhaps the most deeply charged field because we live in a death-phobic culture where fear of our environment as a threat is endemic; discussion of relative risk has always been difficult to grasp.

- Thirdly, context changes the picture, with local and global (and everything in between) issues being significantly different.

- Fourthly, I have a deepening trust in the wisdom of indigenous and traditional peoples of place, including my own ancestors, and a slowly developing but accelerating scepticism about the apparent wisdom of the latest ideas from reductionist science, even when supported by an apparent consensus of experts in a particular field.

Having laid my cards on the table, I would much rather be debating with Monbiot on his claim that wood is incredibly bad for the environment, but thought I should dig deeper in addressing the concerns of permies and retrosuburbanites about wood smoke and health beyond what I did in RetroSuburbia. However, as always in permaculture and holistic decision making, we’ll start with the context to design from patterns to details.

What is the context?

Just because wood burning might be a major cause of ill health and reduced life expectancy for women cooking traditional food over a smoky, flueless, indoor fire burning green wood or cow dung, does not mean it is a significant contributor to morbidity for otherwise healthy people using moderately well-designed wood heaters burning seasoned wood to supplement passive solar retrofit in the suburbs of Melbourne. Nor Austrian apartment dwellers getting all their winter heating from wood pellet burning basement furnaces, which are well ahead of the most stringent European clean air standards and show ongoing improvement over time.

Since air pollution from burning is largely a product of incomplete combustion, the difference in efficiency of burning to useable heat in these three examples could range from around 10% or less for the hardworking woman cooking for her family, around 70% for the typical “modern” wood heater in suburban Melbourne and over 90% for the Austrian pellet furnace.

Ironically, a simple rocket stove suitable for construction in a suburban backyard or a third world village can almost match the latest computer-controlled wood burning tech (especially when fed sticks at a regular rate by an attentive child contributing to the household and learning about the value and dangers of fire).

Obviously, we have been intimately exposed to wood smoke ever since our Homo erectus ancestors learnt to control fire between 1.7 and 2 million years ago. Working from first principles, about 80,000 generations is a long time for humans to adapt to this enhanced exposure to wood smoke over and above what our more ancient primate and mammalian ancestor creatures absorbed from natural fires. This doesn’t mean humans are immune to wood smoke toxins, but I remain sceptical that wood smoke, or more specifically the small particulate matter (as measured by PM10 and PM2.5 metrics), is equally toxic to the fine particulate matter from burning fossil fuels that we have been exposed to for only 50 to 250 years (10 generations at most).

In early industrial cities of rich countries, particulate pollution was recognised as a health hazard, especially leading to lung disease. This was the motivation for both planning laws to separate factories from residential areas with zoning (and thereby using more fuels to transport workers travelling to work) and environmental controls to reduce pollution beyond that achieved by economically driven improvements in efficiency. These changes over the last 150 years, as well as advances in medical treatment, have probably prevented even the small amount of adaptation to fossil fuel pollution that might have been expected since industrialisation.

In RetroSuburbia I supported my scepticism about wood smoke being as bad as fossil fuel smoke by referencing studies showing only marginal increases in lung disease in Australian and North American firefighters exposed to massive amounts of smoke (p.114). However this historical focus on lung disease has shifted to greater concerns about heart and blood circulatory diseases that are now thought to be caused by fine particulate matter (smaller than 2.5 micrometres and designated PM2.5) that pass from the lungs into the blood. As a result, PM2.5 measurement of outdoor, and increasingly indoor, air has become the most important metric in measurement of air quality. It should be noted that this measure includes all particulates of this size, including dust, dust mite allergens, mould spores, and bacteria along with tobacco and wood smoke, cement dust and fossil fuel emissions particulates. Overall ambient particulate matter is ranked as the sixth leading risk factor for premature death globally.

This focus on PM10, and even more so on PM2.5, as the prime metric for reducing the enormous complexity of what constitutes good and bad air reflects both the reductionist paradigm that dominates scientific culture and research, and the need of bureaucratic governance systems for universal measures against which to judge action to mitigate the substantial impacts of air pollution. If particulate pollution is as important as the scientific and governance consensus suggests, then it is important to acknowledge the role of both land degradation and the power increase from fossil fuels in stirring up dust of all kinds that make up the particulate pollution.

Dust, like wood smoke, was obviously part of life for our ancestors but, like wood smoke, it must have increased markedly with the clearing of forests, ploughing of land, overgrazing and regional climate change leading to desertification. Obviously dry windy environments have more dust than moist sheltered ones. Today large numbers of people inhabit dry dusty places that could never have supported such populations without intensive agriculture and globalised trade; for example, Saudi Arabia with over 36 million people. So historical and continuing land degradation plus fossil fuelled globalisation must have massively increased human exposure to dust as a major element of particulate pollution, especially in some poor and remote places where people also burn wood inefficiently to cook and keep warm.

In more industrialised and urban areas, as well as along transport corridors, the power of fossil fuels used to transport people and goods, drive industry, crush rocks, create bricks and cement and so on all contribute to more dust and keeping that dust in the air. While this should be self-evident, as with industrial noise pollution being a by-product of high energy society, particulate pollution from the application of energy is too. These adverse impacts accumulate for the global working-class who live and work in proximity to these processes.

Meanwhile the elites, and the comfortable but fearful middle class of the world, increasingly isolate themselves from this dust, biological contaminants and combustion by-products by manifold variations of the “tall smokestack syndrome” whereby the problem of pollution is pushed further afield, and in the process often creates more diffuse, deferred and remote problems. By globalising industrial production in China and other developing countries, the rich world middle class had access to new consumer goods at cheaper prices, without the pollution or the resulting guilt, while their working-class brothers and sisters lost their secure industrial employment and became subject to a downward spiral of nationally self-inflicted and environmental ills that paved the way for the politics of division and resentment that the comfortable middle class blame on Trump.

Clearly everything is connected, but a whole-systems perspective is required to make sense of the patterns that reductionist science is systemically blind to.

Permaculture ethics and design principles protect us from the folly and evils of the tall smokestack syndrome and bring the problems created by our own actions back home, forcing us to face them with a combination of circular system design, and behaviour change focused on sufficiency rather than excess (enlivened by a dose of frugal hedonism). In the process, we discover that the diverse wisdom traditions of our ancestors taught the same formula for a meaningful and ethical life.

At Melliodora we accept any pollution we create from smoke, particularly if it gets in our drinking water, as our problem rather than exporting it around the world and onto future generations. This smoke comes from burning 10 tonnes of well-seasoned wood a year to process food, cook, heat water and provide supplementary space heat for a small household, plus visitors, workers, tour and course participants. As the daily fire starter, I am probably subject to more indoor air pollution than my partner Su Dennett who does most of the cooking on our Australian manufactured Thermalux stove that we operate without a stove hood exhaust system. Despite the fact that the wall above our stove leading to a high vent must be subject to much of the wood smoke generated internally most days of the year for 35 years, the single repainting of that wall was not because of wood smoke staining.4It’s also important to note that when we built Melliodora in the mid 1980s, we did our best to avoid building materials that release VOCs, used natural paints and earth-based renders and minimised the use of synthetic furnishings and other materials that we understood were bad for indoor air quality. These synthetic materials are also lethal in a house fire, and given we built our house to be a refuge against bushfire this is of great importance to us.

We acknowledge that there is also a very small contribution of extra pollution to our residential neighbours, most of whom burn less or no wood but, for example, mostly buy their bread, preserved fruit and other processed foods from the supermarket which causes pollution of diverse forms elsewhere. While it might only roughly correlate to air pollution, my own calculations that our bottled fruit has less than 5% of the GHG emissions of a purchased can of peaches is indicative of how bringing the problems back home into the household non-monetary economy can also radically reduce total adverse impacts.

What is the evidence?

Okay, so much for some of the big picture and philosophical perspectives. But is there any hard evidence to support or contradict the idea that wood burning should not be a permaculture solution, let alone banned?

In his article, Monbiot acknowledges The Guardian environment editor Damian Carrington’s reporting as a strong influence compounding his doubt about the sustainability of his wood supply and that his wood heaters may have exacerbated his asthma. The chimney smoke levels when he shut down the heater also contributed to him losing faith in wood as a heating solution and his current position that wood heaters should be banned. These three personal concerns could be part of his valid experience, but being an evidence-based thinker, his call for a ban must be based on the evidence. The prime link is to an earlier article by Carrington (2021) “Wood burning at home is now biggest cause of UK particle pollution” referencing a UK government study. The fact that 15% of the particulates included are from sea spray increased my scepticism of all the included particles in these measures being harmful to health. I persevered and scratched the surface of the 50 page report Mitigation of UK PM2.5 Concentrations. This stuff is incredibly complex and it would take someone with much better science training than me to assess half of the assumptions, methods, findings and options, but I did learn that ammonia gas, mostly from intensive animal agriculture and fertilizer, contributes to PM2.5. A research paper from 2019 on costs and benefits of ag ammonia abatement options quotes other studies showing 40% or higher contribution to PM2.5 in many European countries. This may be an additional reason behind the attempt to close down large swathes of livestock farms in the Netherlands.5Mostly driven by court action to protect natural areas from pollution, see Boztas (2021) article in The Guardian, “Netherlands proposes radical plans to cut livestock numbers by almost a third”

Ammonia (NH3) can combine with volatile organic compounds (VOC), nitrogen oxides (NOx) and sulfur dioxide in the air to form health-harming small particles (PM2.5). Source: Gu et al. (2014). Agricultural ammonia emissions contribute to China’s urban air pollution. Frontiers in Ecology & the Environment. 12: 265–266. Illustration: © iStockphoto.com | [email protected]

I will return to this rabbit hole later, but now, back to the government report which Carrington references for his claim that wood in both closed and open fires was responsible for 38% of the UK PM2.5 pollution.

A linked government document defines Domestic Combustion in this way:

This sector is dominated by emissions from fuel combustion in the residential sector, including for fuels such as coal, SSF, wood, natural gas, gas oil and LPG.6UK Department of Food, Environment & rural affairs (2021/2023) Methods and quality processes for UK air pollutant emissions statistics p.35 pdf download

It appears Carrington may have mistaken the category Domestic Combustion to be a synonym for “home wood burning” when in fact it includes all fuels including very dirty ones such as coal. If only 8% of the population burn wood, as quoted by Monbiot, then most of the pollution in this category must be from other fuels.

Further, the following graph taken from the same document shows Domestic Combustion as somewhere around 26% of the total UK PM2.5 pollution.

I am frankly surprised that I would find such obvious holes in the evidence used to brand wood burning as dangerous in The Guardian articles. Isn’t that the job of their fact checkers?

But then I found another study from the European Respiratory Journal from 2015 that shows sector contributions to PM2.5 in EU15 countries (more affluent western member states). The contribution of domestic wood stoves increases from 25% in 2000 to 38% in 2020 which accurately matches the claim by Carrington, who maybe just got his sources mixed up! But wait a minute; how could a study from 2015 have data for 2020? The source of the data was a scenario planning paper7Amann et al (2015) Baseline Scenarios for the Clean Air for Europe (CAFE) Programme Final Report pdf download from 2005 predicting the likely levels in a context of substantial expected reduction in total PM2.5 pollution.

At this point in my research I thought I would stop digging deeper into what is clearly very complex territory – however for permies or anyone grappling with decisions that are good for their own resilience and health, and that of their community and the planet, it is important to recognise that all so-called solutions have downsides and in general ones that bring the problems back home are more ethical and functional in the long term than ones that push them away or defer them through higher level complexity. Certainly we should not be brow beaten into accepting that “The Science” proves that wood burning is bad, and that the alternatives promoted by the corporations and governments are somehow better. Maybe some independent investigative journalist might want to look more closely at this now long-standing push to demonise wood energy.

What can be done?

Concerns about wood burning could be better focused in places where people depend on it for cooking, fuel sources are depleted and the pollution burden for women and children is high. Support should be given to NGOs, large and small, involved in the spread of simple, efficient and clean burning, locally made rocket stove technology such as Aid Africa or smokelesscookstovefoundation.org. If Monbiot and his British readers wanted to support something more relevant to their own citizens as the UK spirals down into energy poverty and people start burning furniture (literally) including the plastics to stay warm and cook, they could promote and model modest self-build appropriate technology such as this Rocket Mass Heater on a permaculture project in Kosovo.

They could also organise and host neighbourhood Rocket Oven building workshops to help feed and warm the coming hordes of homeless once the knock-on effects of NATO’s war with Russia really start to make life tough. Perhaps The Permaculture Association or similar organisations might already be doing so.

It would be great if someone as influential as Monbiot could recognise that, in the scheme of things, PM2.5 emissions from existing UK domestic heating (good, bad and ugly) by 8% of the population should be way down his list of threats to write about, even if he personally wishes to trade the resilience of his current wood heaters for a heat pump running off the excess wind and solar he hopes the global corporates will build and run. Beyond awareness of threats, Monbiot should know that prohibition of anything that is deeply embedded in people’s personal experience or collective cultural psyche never works. The privileged, who he says are the majority of current wood burners, will continue to do so and nothing will stop the destitute.

Returning to that rabbit hole about ammonia emissions being the source of 40% or more PM2.5 pollution, maybe Monbiot could get together with biodynamic farming pioneer and organic agriculture leader Patrick Holden to work out more equitable and effective ways to radically reduce emissions from intensive meat production and artificial fertilisers. This would be an alternative to crashing food production capacity in Europe and taking over farmland for development, as seems to be the aim of the current Netherlands government war with their farmers. If the gulf between vegan Monbiot and livestock farmer and advocate Holden was too big, then maybe my old mate Peter Harper, long associated with the Centre of Technology in Wales and contributor on landuse and diet to the original Zero Carbon Britain Plan might be able to help stitch together some sort of common vision that didn’t demonise people for their personal habits. Peter’s long-standing vegetarianism and belief in the role of biomass in a Zero Carbon Britain might be just the touch needed.

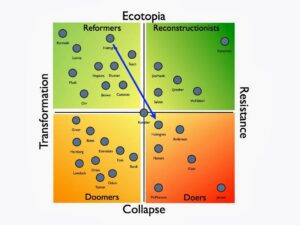

Beyond the personalities, positions and the polemics, I just wish that Monbiot would build on his legacy of being able to change his mind and recognise that the majority of the global green movement is progressively finding themselves as advocates and agents for very powerful but loose and competing networks of interests attempting to use a lockdown-and-straightjacket solution to the manifold global crises. Fears of both real and imagined threats are the sticks (along with a few tired-looking carrots) to corral the shrinking middle class into a technospheric bubble. What concerns me the most is that radical climate activists are being groomed to be the shock troops for this process as the crises deepen. It starts with leading by example with virtue signalling symbolism and moves on to actions that are directly against self-interest (such as reducing resilience by scrapping wood heating and going all electric). It then proceeds to loud judgement of others and demands for top-down controls. The final stages would be vigilante action focused on punishing the resistors and destroying the alternatives.

While I welcome and hope for discussion across the widening chasm that is opening up in the global green movement, my path is clear. At a recent men’s Rites of Passage event, I overcame some of my inhibitions about ritual and ceremony, which in this case included fire. I recognised that my lifetime work with understanding fire in the landscape, bushfire resilient design, fire in the hearth and workshop, ecological forestry, woodwork and wood energy were missing the core of ceremonial fire and the connection to the fire in our hearts. One of many gifts for me from the dedicated men who developed, led and participated in the Passage was closing the circle of fire around our hearts. In saying this I am clearly saying I will live and die regarding fire as an intimate friend and ally that links us to our ancestors, and the gift of the smoking ceremony by Indigenous elders welcoming us to Country.

Addendum

In the process of researching this piece, I wanted to find out if there is any correlation between wood burning per person and air pollution in different countries. I selected three rich countries and four poor or industrialising countries and checked their average annual concentration of PM2.5 pollution, which is the prime metric used by governments and WHO to compare policies and actions to reduce air pollution. The WHO guideline for health set PM2.5 concentration at less than 10 microgram/m3 of air. Over 90% of the world’s population live with air polluted with more than the guideline.

Here are the figures:

Sources:

Av. PM2.5 air pollution from OECD.Stat

Data for total national and household firewood consumption from UN Data

Discussion

The rich countries are at or below WHO levels, the other four are all 3 to 6 times the acceptable levels of pollution. So is there any correlation between total wood burning and pollution? Clearly not, even though the second and third highest PM2.5 pollution countries are also high in wood burning. Sweden is the standout with 5 times the wood burning of India (per capita) with one eighth the level of pollution. Even the UK with 78% of the wood burning of Indonesia (per capita) has less than a fifth of the level of pollution. These figures show no correlation between wood burning and level of pollution.

What about household wood burning and pollution? Again, there is no correlation. While indoor air data is not available and any averaging would be very problematic, various studies suggest a strong correlation between indoor and outdoor air quality, probably stronger in lightweight open houses in poorer tropical countries.

The rich countries have at least three advantages in controlling PM2.5 pollution levels, including:

- better standards and practises and more expensive pollution control technologies especially on large point sources such as power stations etc

- less heavy manufacturing, mining and other dirty industries, especially compared with China and India

- less natural dust due to moister climates,8Australia is also a dusty country, but most people live in the higher rainfall, better vegetated and irrigated urban areas with quite low levels of natural dust (except after massive drought induced dust storms that rarely affect coastal cities). and less land degradation, especially compared with large parts of India and China.

Comparing the rich countries, Sweden has more forested land (not suitable for agriculture) than Britain, a lower population density and a colder climate so it is natural for it to burn more wood per person than Britain, which in turn burns more than Australia with milder climates. The much higher efficiency of Swedish wood burning technology could be a prime factor in Sweden having better air than the UK. Despite the lower population density in Sweden, most housing is apartments with district heating plants (supplying piped hot water) managed by technicians resulting in more usable heat per tonne of wood. Differences in other pollution sources such as the balance of power generation, vehicle emissions plus lower population density could also be important in Sweden’s low PM2.5 level.

There is an anomaly in this data set with household consumption in Australia being slightly higher than the UK despite the milder climates. I attribute this to a higher proportion of households in rural and regional Australia having access to wood from native forests, often outside the monetary economy, while in Britain the more intensively managed landscapes with less forests provide few opportunities and more expensive firewood.

However Australia stands out in having the most potential of the rich countries to greatly increase its use of wood for process energy in value adding agricultural products, industrial processes and domestically for heating (in cooler regions) and cooking (everywhere). By adopting Swedish-level technology, we could reduce pollution in domestic systems, especially with basement pellet furnace systems in apartment blocks (although the on/off nature of southern Australian winters makes management more complex). Building on the suburban BBQ culture, both charcoal and rocket stoves could play a greater role in using fuel generated from landscape waste management.

Thinning regrowth forests around settlements for bushfire safety will open up huge opportunities for grid connected power and agricultural and light industrial “process heat” as well as wood gasifier light truck transport.9See Holmgren (2020) “Bushfire resilient land and climate care” Over time, reafforestation and better forest management could see Australia as the Sweden of the southern hemisphere in terms of wood energy while maintaining good air quality. Better, more intensive management of forests could over time reduce the scale and intensity of bushfire, offsetting any reduction in air quality from increases in domestic burning in less-than-optimal technology.

Britain will be limited by land use conflicts in providing wood on a substantially larger scale unless there is a major reduction in livestock farming, converting pasture to biomass plantations. Limiting pollution would require implementation of technology similar to Sweden. In Sweden, despite the already high use of wood, growth of wood energy in the last 20 years has been substantial while technology has improved. Further gains in efficiency are less likely so further reductions in pollution may also be marginal, while more area in forest or more intensive harvesting would start to erode ecological, landscape and agricultural amenity.

The poorer countries of Indonesia and Congo have a tropical climate but a lot of forest clearing and burning producing very large amounts of PM 2.5 pollution at scales that even affect populations remote from the fires. Reafforestation of degraded grazing areas, especially with fast-growing naturalising trees could increase the total forest resource base and support expanded use of wood energy, including localised power grids, small industry and transport replacing depleting and expensive oil and gas resources (especially in Indonesia). With weak governance structures, sustainable management of the resource base could be the limiting factor.

China and India are heavily industrialised and increasingly urbanised, concentrating people in areas with high pollution.

The high level of wood burning in India and Indonesia includes many industries such as brick making as well as high levels of household burning primarily for cooking but also warmth in parts of India. More efficient wood burning technology would probably have more net health benefits than in the other countries and, in India, would make a major contribution to reducing depletion of wood resources and distance to transport (whether by foot, cart or truck). Wider use of traditional sun-dried adobe bricks would reduce the need for fuel to fire clay bricks or make cement for concrete.

These comments on the data and suggestions show how one size doesn’t ever fit all and, while it can be useful to gather and use better data to understand those differences, we should remember the primary importance of context. My off-the-cuff suggestions are my first big picture exploration with much greater confidence in making them for the rich countries, especially Australia where I have long standing interest, contact and practical experience in the subject.

Hopefully my oscillation between the big picture holistic context perspective and diving into the details helps others see how the permaculture design principles Observe and Interact and Design from Patterns to Details suggest this process identified by the late Dan Palmer as involving the culturally familiar “inspecting” (zooming into details) but also “aspecting” (standing back to see the larger picture).10For a further examination of this concept, see Advanced Permaculture Planning and Design Process 2017 – Part Four, part of a long discussion on David Holmgren and Dan Palmer’s personal design process journeys at makingpermaculturestronger.net.

14 thoughts on “Is wood smoke the new evil?”

I love the way you have been prepared to give a balanced response based upon evidence and being truthful about complex details that were outside of your scope to investigate or evaluate further. In relation to the data on the Congo ( I lived there for a couple of years) it is worth noting that they burnt off huge areas of grassland every dry season, a tradition for many other indigenous people as well. These ‘bushfires’ were huge and the smoke particles released into the atmosphere spread far and wide. the smell of burnt charcoal is a memory of African culture you don’t forget. It seems to me that a lot of the research used in the argument against wood fires originates from selected sources close to home rather than embracing the global context. I find it hard to believe that wood fires and farting cows cause so much toxicity when many of my neighbours drive cars the size of trucks.

There is ample evidence about just how toxic and costly domestic wood heating (DWH) is in urban areas in Australia. Wood smoke is a cocktail of carcinogens and particulates such as PM2.5 which are fine and lodge deep in the lungs. These particulates and smaller are now regarded as particularly health hazardous. Health costs of DWH in NSW and Vic are estimated to be in the billions of dollars over 10 years. This is equivalent to thousands of dollars in health costs per heater per year. Check out papers by air quality expert Dorothy Robinson et al. on the web in the journal Atmosphere in 2020 and in the Medical Journal of Australia in 2021, including the supplementary info document. Research on the attitudes of DWH users shows that many have little awareness of, and a reluctance to acknowledge, the harmful effects of wood smoke. The “warm glow” factor overrides scientific facts about harm. There is no safe level of exposure to this form of particle pollution. People with asthma are the canaries in the coal mine, often complaining of serious adverse effects, with attacks triggered by smoke. Others are likely being harmed without even being aware of it. Smoking in public places and offices was banned two decades ago. The ACT Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment has just produced a report recommending a ban on installing new wood heaters in urban suburban areas. Not before time.

Actually Murray, while there is lots of evidence of harmful effects of particulate pollution there is very little about the effects of particulate pollution from woodburners. While the use of particulates as a measure of air pollution might be useful and relatively consistent in Europe where the air pollution is (was?) dominated by fossil combustion, the same can not be said for other parts of the world. Just looking at what particulates are measuring should give you pause for thought – it is measuring simply the mass of particles that get through a certain size filter with no reference to their chemical composition or the number of particles: one grain of salt is assumed to be as toxic as 1 million ultra fine particles with all their adsorbed PAH nasties. Of course the ultra fine particles can get through the lungs and into the blood, whereas the larger particles don’t get past the lungs.

Here in NZ the original HAPINZ study (Health and Air Pollution in NZ) found that the dose-response ratio for health effects from different particulate levels was 400% different summer to winter in Christchurch – of course the summer particulates contained almost no woodburner particulates and was dominated by fossil combustion, while winter was dominated by woodburner particulates.

And the local Health board here in Nelson in scratching around for evidence for ill health from woodburning used the Launcerston Tasman study, but I was appalled to find that that study found “the period of improved air quality was associated with small non-significant reductions in annual mortality”. Here in Nelson PM10 particulate levels were crashed in every airshed in Nelson though burner bans by between 65 and 72%, hospital admissions for respiratory diseases per capita went up over the same period by 25%.

However don’t get me wrong I’m not saying air pollution form woodburners is not harmful – it does contain many of the same species of PAH* that fossil fuel combustion have but in evidence in an Environment Court ruling into the Southern Link for Nelson was shown to be 1/10 in number compared to fossil combustion.

So what I think we shoudl be doing is instead of having burner ban, ban smoke. Any good woodburner, especially the ultra low emission burners widely available in NZ now, burning dry wood should produce no smoke after that initial firing.

It seems clear to me that cold damp houses were more harmful to health than woodburner particulates. And while is is actually pretty easy and well understood now how to build new houses that need absolutely minimal heating in winter in any climate in NZ or Australia, it is literally impossible to make existing houses as insulated with no thermal bridges and as airtight as these new houses. This is where there is I think a role for use of ultra low emission (wood) burners. And they are certainly good for resilience from electricity grid outages that are becoming more frequent and severe with climate change.

*PAH = Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Thanks Peter for some relevant additional evidence to resist the push to ban wood heaters in urban areas. I would appreciate sources for the evidence you mentioned especially the 1/10 level of PAH in wood smoke compared to fossil fuels.

Where’s the actual citations? There’s a lot of text and comments on here, but not a lot of actual verifiable evidence from people who are doing the work to make sense of these issues with the scientific tools we have at hand. By that I mean, using quantitative science. I reckon it’s worthwhile reading what scientists have to say, rather than dancing around the issues and having a go at people like Monbiot for pointing out hypocracy (in this case his own).

Here’s a few articles that say a lot more than what i’ve seen on here – https://theconversation.com/like-having-a-truck-idling-in-your-living-room-the-toxic-cost-of-wood-fired-heaters-140737

– https://theconversation.com/imagine-the-outcry-if-factories-killed-as-many-people-as-wood-heaters-207411

I gotta say, I’m pretty disappointed in the arguments put forward on this post and the comments. cherry picked statistics and analysis of what are inherently complex dynamics using anecdote with a veneer of systems thinking doesn’t stack up for me.

Based on the comments it looks a lot like a bunch of people trying to justify why they don’t want to accept the ramifications of what we (yes I also use wood for heating) are doing. when faced with a fundamental change to how we live we can either accept what our best understanding tells us, in this case, the multiple disciplines of science that all point to the need and opportunity of moving on from our love of fire, or risk becoming a denalist. I suggest looking at whether your skepticism of the science is objective, or are you building straw men arguments because you’re falling into the trap of denialism?

I appreciate there are issues with air quality from wood heaters, as well as issues about the sourcing of wood for the heaters and issues about the poor design of houses to begin with. I do not dismiss those issues lightly. But is not the controversy about wood heaters a distraction from the yet to be resolved issues associated with products manufactured by fossil fuel companies?

Derek – certainly not a distraction, as global warming emissions from wood heaters is important too. This letter in today’s 6 April 23 Canberra Times shows that wood heaters in urban areas are a health disaster.

The right to breathe

Asthma sufferer and Tuggeranong resident Caitlin Ross describes her wood-smoke-provoked asthmatic attacks as “Like sucking air through a straw”, (“Asthma Australia backs push to ban wood heaters in ACT”, canberratimes.com.au, April 2). This is no exaggeration; we asthmatics are all too aware of this agonising feeling. Those insisting on burning wood should try breathing through a straw for a minute.

Would a ban infringe on civil liberties? Can there be a more fundamental civil liberty than the right to breathe any air, preferably clean?

As the article clearly suggests, the scientific evidence is already compelling and multifaceted. No more dithering and procrastinating.

Legislate a ban now. Tomorrow we’re dead. Literally.

Jorge Gapella, Kaleen

sorry to hear about your asthma Murray

I personally don’t have asthma Derek, but pasted a recent letter to the editor from someone who has.

Asthmatic here with wood fired heating with neighbours with wood fired heating semi rural

I have more trouble in spring with the wattle blooms than wood smoke

To tell the absolute truth in spring I regularly end up on steroids to bring my asthma under control.

I never have this problem in winter.

This is my experience

I have been running a wood stove to be the primary heat source for my home for 3 years now. I have natural gas and some electrical heat as a backup. In the part of the world where I live heating during the winter season is absolutely necessary. I am able to do that with a locally available waste product, trees felled in the normal maintenance of this semi-urban area.

A wood stove leaves me responsible for sourcing the fuel and the pollution it creates. Whereas by backup heat has no relationship with the effects of sourcing it. I also know that I will have the ability to heat my home in pretty much any circumstance.

I consider wood heat to be an essential resource and do my best to make efficient use of it in my home.

Thanks David for your thoughtful essay on wood as domestic fuel. Our family lives in a very similar wood-cooking model as yours, the main difference being that we cook with charcoal when the big stove isn’t on.

The issues you raise about domestic cooking are intimately entangled with the huge questions about forests, fire and humans that we have in Australia. I fear that the regulatory approach trying to control human exposure to smoke toxins is likely to take us out of the frying pan and into the (forest) fire.

If we’re worried about smoke from domestic fires, we’re likely to be even more worried about smoke from fires in the landscape. Adding escalating air quality concerns to our current model of forest management, increases the focus on total fire suppression, seeing fire as always an emergency rather than part of the ecology. Under this paradigm, our forests are changing, losing their grassy ground covers under a heavy understorey, with big trees suffering dieback (often to the ringing of bell birds here in SE Qld). Fires are infrequent (often decades between), but when they occur it tends to be during drought and fire is very hot, destroying ancient trees, scorching soil and stimulating a heavy new understorey of wattles, cypresses, etc., to fuel the next fire. The Black Summer fires in 2019 illustrated the failure of this model, not only wrecking an unimaginable area of forest but also delivering huge doses of smoke to millions of people over months. We have no plan for how to avoid the next Black Summer.

Aboriginal landscape management, using frequent cool fire, maintained a more open forest structure, unlikely to support high intensity fires. When we try to learn from the Aboriginal model and restore the traditional forest structure, we find our forests are greatly over-stocked with small trees. We need to do a lot of cutting and then deal with huge amounts of wood fuel before cool burns can be safely used through the forest to restore grassy ground covers. Wood-burning households then become a way of disposing of heavy wood fuels with less smoke and less soil damage than burning them on the forest floor. The kitchen cook-stove becomes part of the forest’s carbon cycle with mutual benefit.

In summary, I think the question here is whether we can plan to solve our problems with centralised technocratic control: over fire in the forest, over people’s household systems, and in favour of command and control forest fire management and energy grids; or is this a failing model that will leave us to return to decentralised sources for energy and localised skills and culture for forest management.

Professor Guy Marks was recently interviewed on ABC TV. He is a respiratory physician and epidemiologist. He said wood heaters contribute a significant amount of particulates to the atmosphere and a danger to the community. I think some of the comments above just don’t want to face the facts.

I think you are beginning to sound like a troll. You have made your point and are cluttering up the comments section with what appears to be a personal agenda. Oh and it’s boring too.

I agree that the distributed and controlled burning of wood through high quality combustion home stoves solves in a large way the issue of greater physical harms (asthmatic or more severe) from uncontrolled forest fires. So far the government has not found a solution except large scale back-burning. I am sorry for people with breathing issues though.